You can read about indirect free kicks elsewhere on the site, exploring what they are, what they’re given for and how they can influence a game. Here we’ll have a look at their far commonly used relative the direct free-kick.

Most of the time in a match when a free-kick is given then it’s likely to be a direct free-kick, which means that the taker can score a goal from wherever the kick is taken from without another player having to touch the ball first.

It comes about because of Law 13 in the IFAB Laws of the Game and there are numerous procedures around the taking of a free-kick, with the most crucial one being that if the ball is kicked directly into the goal from the kick then a goal will be awarded.

That’s in contrast to if the same thing happens from an indirect free-kick, when a goal kick is given in the same circumstances. Equally, if an own goal is scored from either a direct or indirect free-kick then a corner is given. Here’s a closer look at the rules over direct free-kicks.

How Direct Free-Kicks Work

Direct free-kicks are awarded for the majority of fouls in football, from handballs to bad tackles. In fact, there are far fewer infractions of the rules that are not rewarded with a direct free-kick than those that are.

The list of direct free-kick offences includes, but is not limited to, the following:

- Kicking or attempting to kick an opponent

- Tripping or trying to trip an opponent

- Pushing an opposing player

- Holding a player on the other team

- Impeding the movement of an opposition player via physical contact

- Deliberate handling of the ball by any player that is not the goalkeeper

- Jumping at an opponent

- Charging at an opponent

- Tackling with excessive force

- Spitting at an opponent

If a player commits an infringement that fits into any of those categories as well as a number of others that aren’t listed then the referee will award a direct free-kick. In addition to this they might well choose to also either book or send off a player, but that decision makes no difference to whether the free-kick awarded is direct or indirect.

The crucial place on the pitch when it comes to committing a free-kick offence is within the defensive team’s penalty area. If the defending team commits a foul that would be a free-kick elsewhere on the pitch then the referee will award a penalty kick. It’s worth noting that not every foul in the penalty box is a penalty offence, with indirect offences, such as a goalkeeper picking up a ball passed back to them deliberately by a player on their team, being an indirect free-kick offence and being awarded as such.

The Procedure Of Direct Free-Kicks

As mentioned, a direct free-kick offence committed by the defensive team in their own area results in a penalty kick being awarded to the attacking team.

Anywhere else on the pitch, however, and a free-kick is given. The kick must be taken from where the foul was committed, but it’s up to the referee to martial this. You will often see players attempted to ‘steal’ a few yards for the free-kick, with weak referees failing to stop them.

The ball itself needs to be stationary before being kicked, with the more picky referees often taking play back if a team attempts to play a quick free-kick and they perceive the ball to be moving as it’s struck.

Defensive players need to be located at least 10 yards from the place the free-kick is being taken from.

The Vanishing Spray

A quick note at this point regarding the vanishing spray that referees use during top-level matches. The spray was invented by a Brazilian named Heine Allemagne in 2000, being used for the first time in a match in the Brazilian Championship the following year. It was soon adopted in Brazilian competitions and the patent on the spray, which was named Spuni, was granted in 2002.

Interestingly, it still took over a decade for the spray to find its way into common usage in the upper echelons of the game. It had been in use during the Copa América and Major League Soccer in 2011 but the first time that it came to prominence for the majority of football fans was when it was given its inaugural usage on the international stage during the 2014 World Cup hosted by, fittingly, Brazil.

The spray used for tour tournament was a commercial version known as ‘9-15’ and developed by an Argentinian named Pablo Silva. Controversially, FIFA have not paid royalties to Allemagne for the use of the spray that he developed, despite the fact that the Brazilian courts have ruled in his favour on the matter.

Since the World Cup it has been used by most of the world’s major tournaments, including the Bundesliga in Germany, Italy’s Serie A, La Liga in Spain and the Premier League.

The idea behind the spray is that it stops attacking teams from moving the ball forward because the referee marks the place that the ball should be for the free-kick, as well as stopping the defending team from altering the position of the defensive wall. Referees usually count out the ten yards that opposition players need to be away from the ball before putting a line down with the spray to ensure that they don’t encroach.

The spray has the appearance of being like watered down shaving foam. It is designed to leave no discernible trace on the pitch after its use, having been sprayed from an aerosol can by the match referee.

Referees are not forced to use it, instead using their discretion regarding whether or not it’s necessary to so so. Usually they’ll use it if the free-kick is in a position where the attacking team will have an attempt at goal from the free-kick. The spray disappears after a minute of being applied.

Quick Free-Kicks

It is usually at the discretion of the referee as to whether or not the team awarded a free-kick can take it quickly, which is to say without needing to set up any sort of formation to receive the ball. This will often come down to whether or not the referee is either speaking to, booking or sending off a player after the awarding of the free-kick.

If the attacking team chooses to take a quick free-kick then the opposition players don’t need to be 10 yards or more away, but obviously there is a risk that the free-kick will go wrong and they will therefore lose their advantage.

With a normal free-kick the team that is awarded it can choose to ask the referee to allow them to re-take it if an opposition player is closer to the ball than 10 yards, but they waive the right to ask this with a quick free-kick. Intelligent players will stand in front of the ball and prevent the attacking team from taking a quick free-kick, allowing their team to get set up to defend the free-kick.

It’s a delicate tight-rope to walk, however, given that referees can book them for obstructing the free-kick if they choose.

Defensive Walls

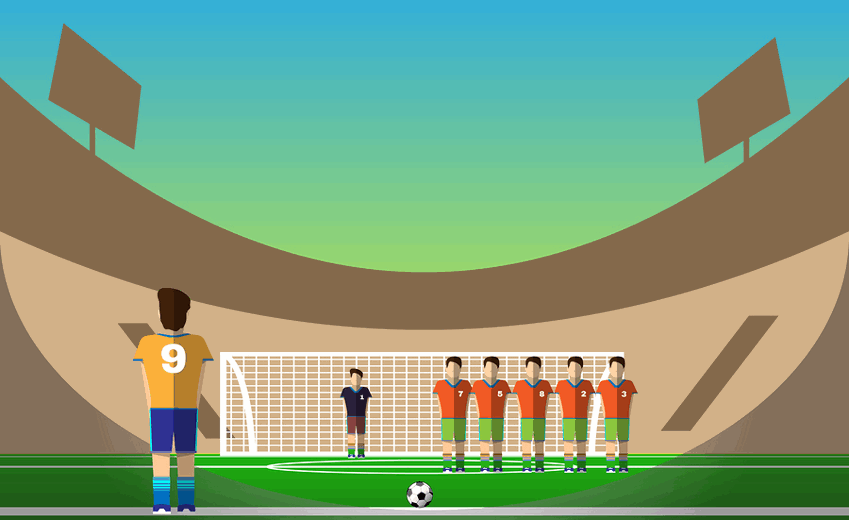

Defending teams are allowed to protect their goal from a free-kick by lining players up in what is known as a ‘wall’.

This is essentially a row of players from the defensive team that can jump as the ball comes towards them in the hope of blocking its path towards goal.

The players stand side-by-side and need to be at least 10 yards away from the ball, which is indicated by the referee using the vanishing spray to let them know how close they can be.

Attacking teams will often put players of their own alongside the wall in the hope that they’ll be able to open up some space for the ball to pass through.

Free-Kick Strategies

As you might imagine, there are numerous strategies used by teams when taking free-kicks. A lot of the strategy that a team decides to employ will depend on where on the pitch the free-kick is awarded.

If it is reasonably close to the opposition’s goal and there is a sight-line available then a specialist free-kick taker may choose to shoot directly at goal. Oftentimes they will attempt to curl the ball around the defensive wall, but sometimes they might be cheeky and try to kick it underneath the wall and hope that the players within it will jump to stop a ball going over them.

One of the more common methods employed for a free-kick, especially if it is given on the far sides of the box, is to ask the tall centre-backs of the team to get into the box before the ball is crossed in in the hope that one of the attacking players can get something on it and ask questions of the defence.

Oftentimes the strategy employed will depend on the player that tends to take the free-kicks for the attacking team. Do they have a goalscoring specialist from free-kicks, such as Cristiano Ronaldo? Or is the team better built to get tall players on the end of a ball floated into the box?

The final method worth mentioning is to attempt to confuse or mislead the defending team by having a player run past the ball without touching it. This player’s movement can sometimes lead defences or their goalkeepers to think that the ball is about to be kicked and they will therefore make their defensive action early or give away their plan. As long as this players doesn’t kick or touch the ball it is an entirely legal thing to do.