So many things in history come full circle, with standing at football grounds being a good example. When football first started being played in England it was essentially just a group of men kicking a ball about. Where they played initially was in any open space, such as a park or on private land. People began to take an interest in the game and turned up to watch the matches, standing on the sideline and offering encouragement to their favoured team.

As time passed and the game became more and more popular so too did the facilities for the ‘audience’. Soon areas where the crowds could sit were erected, allowing people to watch the games in comfort rather than being on their feet for an hour and a half. Nowadays people have to sit if they’re watching the game in England but most football fans are keen to be able to stand again. Here we’ll have a brief look at the history of standing in football before investigating what changed and what may happen in the future.

The History Of The ‘Terrace’

Originally terracing was introduced at football stadiums for the simple reason that they were cheap, easy to build and allowed large numbers of people to use them. At the various stadia in England the areas of the stands that ran alongside the pitch typically contained seats and were relatively expensive to enter.

As a consequence a cheaper alternative was looked for and found by the creation of earthen banks, often made from rubble and rubbish from the building of the main stands. As time went by wooden railway sleepers were placed on top of the rubble in order to give supporters something a bit more stable to stand on. In some parts of the country in the late 1800s and early 1900s bleachers were used, similar to those you might find in American colleges nowadays.

Sadly one such structure collapsed at Ibrox in 1902, resulting in the deaths of 25 people and serious injury to around 500 more. As a consequence a decision was made to ban any terraced section that wasn’t supported with solid earth. Over time these areas began to be made out of relatively cheap and easy to install concrete, with crush barriers made from metal installed throughout the terraced section to stop any crushing incidents from taking place.

The popularity of the terraces undoubtedly came from the cost of getting into them. The fact that it was such a cheap area to go meant that working class people were able to get in to watch their favourite football team without having to pay a huge amount for a ticket. The working class lads who stood on these terraces soon began to give them nicknames, with ‘Spion Kop’ being the most popular. This was in honour of the Battle of Spion Kop that took place in the Boer War. Arsenal’s fans were the first to name their terraced area the Spion Kop, though the one at Anfield in Liverpool became the most famous of them all.

Safety Problems

It is a common misconception of terraces that they were unsafe places to be. This is largely because of the sheer number of supporters who could be crammed onto them, making it difficult to move about freely. However they were mostly safe places to watch a match from and often engendered a spirit of camaraderie and togetherness in their occupiers.

They weren’t always flawless locations, though. When railway sleepers were a popular base for them it was not uncommon for people to slip during wet weather conditions, falling and injuring themselves. Some people would be known to faint in the busy environment, too, with the site of an unconscious body being passed over the heads of supporters to get them to the front of the terrace a not uncommon occurrence.

There were tragic disasters on terraces too. In 1946 33 people sadly lost their lives during a crush at Burnden Park, the then home of Bolton Wanderers. By the 1970s it wasn’t just the sheer amount of people in the ground that made things tricky for supporters. Hooliganism was growing more and more and away supporters would often engage in a practice of trying to ‘take the terrace’ of the home fans. This would involve infiltrating the home team’s terraced area and claiming it as their own, resulting in violence erupting on a regular basis.

As a consequence a decision was made to introduce segregated areas to terraces throughout England. This involved the erection of fences separating the difference parts of the terrace from each other, as well as high fencing stopping people from being able to get onto the pitch. Sadly this contributed in a significant way to the worst stadium disaster in English football’s history, the Hillsborough Disaster.

The Hillsborough Disaster

There is a full article relating to the Hillsborough Disaster elsewhere on this site, so we won’t go into too much detail about it here. It’s important to mention, however, not just because of its significance to English football but also because of the resultant changes to terracing throughout Britain.

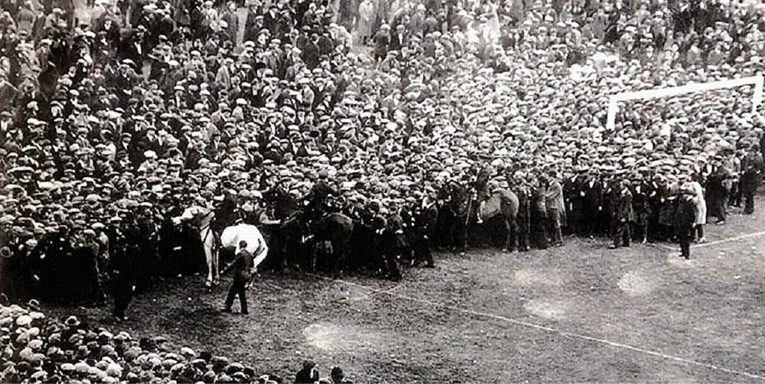

The disaster occurred on the 15th of April 1989. Liverpool were playing Nottingham Forest in the FA Cup semi-final and the neutral venue for the match was Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield, home to Sheffield Wednesday Football Club. The lower terraced section in the Leppings Lane End of the ground was split up into three different pens, separated by fencing. Because of the layout of the ground supporters naturally found themselves going into the central pen, meaning that it was filling up much more quickly than either of the pens on the side.

In previous years Liverpool supporters had been housed in the opposite end of the ground because it was closer to the city and direction the club’s fans would come from. It was also larger than the Leppings Lane End and Liverpool traditionally took more supporters to games than other club. However they were given the smaller section and fans were delayed in getting there because of roadworks and an accident on the motorway between the two cities.

As the game drew closer to kick-off there was a build-up of Liverpool fans outside the ground. Again, this was in no small part due to the fact that in previous years the police had set up barriers to slow the crowd down and to check tickets, something that they neglected to do in 1989. In order to try and relieve the congestion outside the ground the match commander, chief-superintendent David Duckenfield, gave the order to open an exit gate so as to get the Liverpool fans into the ground.

Sadly the entrance to the already over-full central pen was not closed over as it should have been. Neither were there any police officers put in place to direct fans away from the central pen and in to the two relatively empty side pens. This resulted in too many people trying to enter one section of the terrace, with the fans at the front and the sides unable to escape because of the fencing obstructing their movement between the pens as well as out onto the pitch.

96 Liverpool fans lost their lives as a result of the Hillsborough Disaster. 94 of them died on the day with two more dying at a later date. More than 750 people were injured in a non-fatal manner. As a result of the disaster a report into how it happened was commissioned, led by Lord Justice Peter Taylor.

The Taylor Report

The chief purpose of the Taylor Report was to establish the main reason for the disaster, with South Yorkshire Police attempting to pin the blame on Liverpool fans in the immediate aftermath of the disaster itself. Taylor found that to be entirely false, instead laying the blame for Hillsborough squarely at the door of the police and the stadium itself, with the crush barriers believed to have hindered fans rather than helped them.

Taylor was also asked to make some recommendations about the future of the sport and it is these recommendations that we’re most interested in in this section of the site. Taylor declared that standing itself was not ‘intrinsically unsafe’, but felt that all major stadiums in England should be converted into all-seater venues and that every person who attended a football match should be given a seat to sit in rather than being asked to stand.

Taylor also said that turnstiles should be introduced to ensure that fans enter the stadium slowly and to make certain that clubs knew how many people were present in the ground at any one time. He suggested that the sale of alcohol should be limited, too. An odd suggestion considering that he also confirmed that alcohol had nothing to do with the disaster.

Despite Taylor’s statement that standing areas were not necessarily unsafe, the government still decided to ban standing throughout the country. He also said that football clubs should not be allowed to use the fact that stadia were becoming all-seater to drive prices up and should do their best to ensure that the game remained in touch with its working class roots and let people of all ages and social positions enter ground to watch games. Something else that has been forgotten and ignored over the years.

In the wake of the Taylor Report most major clubs across the country either redesigned or outright rebuilt their stadiums. Some of the most famous terraces in English football were removed, including the North Bank at Highbury, Villa Park’s Holte End and Liverpool’s own Spion Kop. Over the following decade some much-loved grounds also closed their doors for the last time, with the cost of refurbishing them to meet the demands of the Taylor Report too expensive when compared to building a new ground entirely.

Safe Standing

The debate surrounding safe standing is one that is likely to rage on for some time yet. Some members of the families of those who lost their lives in the Hillsborough Disaster are understandably reluctant to see standing re-introduced to football, believing that history is sure to repeat itself.

For many others, however, the belief is that nobody lost their lives at Hillsborough because of standing. Instead it was down to police incompetence and a stadium that didn’t even have a valid safety certificate. The obvious alternative is to introduce safe standing as is used in countries like Germany.

At the moment the country’s most popular stands, such as Liverpool’s refurbished Kop, see fans standing in an unsafe manner on a regular basis. Thousands of people stand up for the duration of the match with their chairs behind them, resulting in people falling over and getting injured regularly when something like an important goal is scored. Club’s turn a blind eye to this because it is happening in areas filled with the most passionate and noisy fans.

The model most English football fans want their clubs to follow is that set in Germany. At the Westfalenstadion, for example, safe-standing is in place to allow 25,000 people to fill the Southern terrace on a weekly basis to create Borussia Dortmund’s famous ‘Yellow Wall’. There the seats are able to be flipped up into a locked position, giving plenty of space to stand in front of. The seat then forms part of a ‘rail’ that goes up to the waist of the row in front. These ‘rail seats’ can also be flipped down into more standard seating in order to meet the current requirements of UEFA that all European matches are seated affairs.

The need for all-seater stadiums is only applicable to the top two divisions in England, with Celtic having introduced an experimental 2000 ‘safe seats’ from the start of the 2016-2017 season. Scotland is exempt from the 1989 Football Spectators Act that requires clubs to have all-seated stadia, so if the experiment at Celtic Park goes well it is likely the call for similar safe-standing to be introduced in England will grow louder in the next few years.